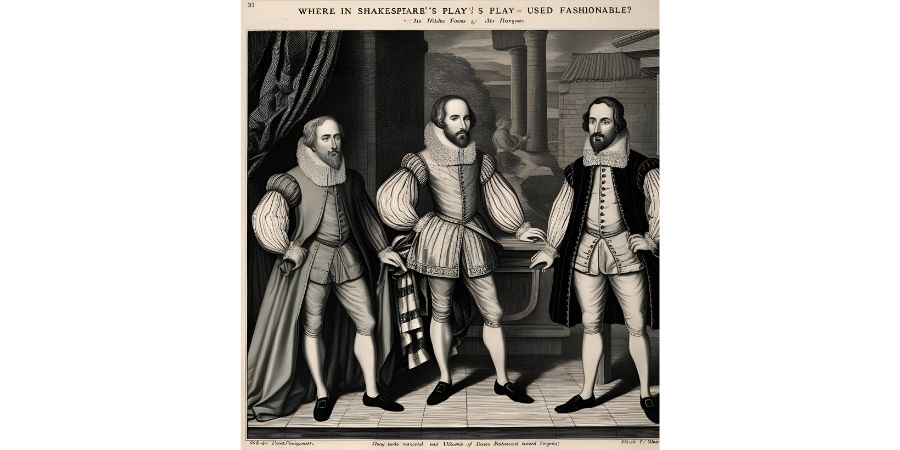

In the vibrant world of William Shakespeare’s plays, fashion is far more than mere decoration — it’s a mirror reflecting identity, power, and societal roles. Whether through intricate descriptions, character dialogue, or costume choices on stage, Shakespeare often used clothing and style to highlight themes of status, transformation, deception, and desire. The term “fashionable” and its conceptual cousins appear throughout his works, signaling not only the outer appearances of his characters but also their inner ambitions and shifting social positions.

During the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, fashion was a powerful language, and Shakespeare, ever attuned to the rhythms of his time, wielded it as a literary and theatrical device. From the richly dressed courtiers in Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost, to the playful gender disguises in Twelfth Night and As You Like It, clothing becomes a coded expression of identity. This article explores how and where the concept of being “fashionable” was used — both literally and symbolically — in Shakespeare’s plays, shedding light on how apparel helps reveal the deeper narratives of power, gender, and performance.

Language of Style: How Shakespeare Used the Word ‘Fashionable’

When we think of the word fashionable today, we often imagine runways, influencers, or the latest trend on TikTok. But in Shakespeare’s time, the word carried slightly different connotations — ones tied more to behavior, social standing, and reputation than to clothes alone. While the exact term “fashionable” doesn’t appear frequently in Shakespeare’s plays, its root word — fashion — does, and it’s used in a variety of contexts that shed light on the Elizabethan mindset.

In Shakespeare’s lexicon, fashion wasn’t just about style or clothing; it was about form, manner, and way of being. The word often appears when characters speak of appearances, imitation, or even deceit. For example, in Much Ado About Nothing, Benedick rails against love making a man “the only man fashionable,” suggesting that adopting the outward signs of romantic affection is a kind of ridiculous performance. Here, “fashionable” carries a bite — it implies conformity, affectation, and foolishness.

Similarly, in Hamlet, the term fashion is used when Polonius advises Ophelia to guard her virtue against Hamlet’s affections, warning her that “these blazes, daughter, / Giving more light than heat… are not lasting; / The perfume and suppliance of a minute; no more.” Though the word fashionable isn’t directly used, the implication is there: love, like fashion, is fleeting and deceptive. It’s a veneer, not a constant.

In Love’s Labour’s Lost, fashion is tied to wit and the pretentious performances of courtly lovers who try to outdo each other in language and appearance. These men are not only trying to be fashionable — they are obsessed with being perceived as clever, cultured, and desirable, revealing Shakespeare’s keen eye for how style can become a social game.

Occasionally, Shakespeare uses the word fashionable to directly mean “in style” or “popular.” In Troilus and Cressida, the term shows up in reference to someone being “fashionable” in speech and manners, which again connects to the idea of putting on a persona — of being shaped by external influences rather than by internal substance.

In short, when Shakespeare or his characters talk about being “fashionable,” they’re rarely giving a compliment. The word usually comes with a layer of irony or critique. It points to the superficial — the temporary — and often warns against trusting appearances. Fashion, in the Shakespearean sense, is as much about the masks people wear as it is about the clothes on their backs.

Cross-Dressing and Disguise: Fashion as Performance

Few things delighted Shakespeare more than a good disguise, and when it came to fashion, clothing became the ultimate theatrical device. In many of his comedies, cross-dressing and costuming aren’t just plot gimmicks — they’re essential to the story’s movement and meaning. Through gender disguise, Shakespeare explored identity, power, and love, using clothing as a tool to blur boundaries and create space for transformation.

Take Twelfth Night, for instance. Viola, shipwrecked and alone in a foreign land, dons a man’s outfit and becomes “Cesario,” entering Duke Orsino’s court in disguise. Her new wardrobe not only protects her but also empowers her to move freely in a male-dominated world. As Cesario, Viola gains access to political spaces, earns the trust of the Duke, and develops a complicated love triangle with Olivia, who falls for her male persona. Here, fashion is more than fabric — it’s freedom, deception, and a source of emotional chaos.

Similarly, in As You Like It, Rosalind disguises herself as “Ganymede” after being banished from the court. Unlike Viola’s disguise, Rosalind’s cross-dressing allows her to playfully explore the rules of love. Dressed as a man, she tests her beloved Orlando’s affections by coaching him on how to woo “Rosalind” — all while being Rosalind in disguise. Her male attire gives her a kind of playful authority and allows her to voice truths that may have been unacceptable from a woman. It’s a clever move that flips gender norms and highlights the performative nature of both fashion and romance.

These disguises also served a double purpose on Shakespeare’s stage. Since all actors were male, young boys played female roles — and when those female characters disguised themselves as men, the actor was essentially a boy playing a girl playing a boy. This theatrical layering made the idea of gender and fashion fluid, highlighting how much identity could be shaped — or reshaped — by outward appearance.

But the point wasn’t just comedy or confusion. Shakespeare used these costume changes to ask deeper questions: What does it mean to be seen? To be believed? To be loved — not for who you are, but who you appear to be? Through the fabric of a doublet or the drape of a gown, characters were able to rewrite their stories, at least for a while.

In these plays, cross-dressing is fashionable in the truest Shakespearean sense — a tool of reinvention, risk, and revelation. Clothing becomes a character in its own right, capable of changing the course of the entire plot.

Courtly Elegance vs. Common Attire: Fashion and Class Distinctions

In Shakespeare’s world, fashion didn’t just reflect personal taste — it was a visible marker of class, status, and even morality. Audiences in the Elizabethan era would have immediately recognized the significance of costume and clothing references on stage. A richly embroidered cloak or a stiff ruff wasn’t just decorative — it signaled nobility, authority, and refinement. Likewise, ragged garments or simple smocks marked a character as a servant, a fool, or someone on the fringes of society.

Shakespeare leaned heavily on these visual and verbal cues. In plays like Hamlet, the court is dressed in dark, somber elegance — clothing that matches the weight of political intrigue and mourning. In Macbeth, regal robes become symbols of ambition and power. When Macbeth takes the throne, he refers to his kingship as “a giant’s robe / Upon a dwarfish thief,” suggesting that although he wears the garments of a king, he doesn’t quite fill them. This image of clothing that doesn’t fit underscores the tension between appearance and reality — a recurring theme in Shakespeare’s treatment of fashion.

In contrast, commoners in the plays often wear practical, earth-toned clothes that set them apart visually and socially. Shakespeare doesn’t shy away from poking fun at this divide either. In Much Ado About Nothing, the comically inept constable Dogberry and his watchmen are clearly out of their depth, and their plain dress emphasizes their lower status. Their garbled speech and awkward manners further exaggerate the comedic contrast between the noble characters and the “fashion-challenged” townsfolk.

Fools and jesters, meanwhile, often occupy a strange middle ground. Their motley costumes — colorful, patched, and exaggerated — make them instantly recognizable, but they also serve as a disguise for their often sharp, subversive intelligence. The Fool in King Lear, for example, may wear the outfit of a clown, but his insights cut deeper than many of the noblemen at court. Here again, Shakespeare plays with the idea that fashion might reveal, but it can also mislead.

Shakespeare also occasionally critiques the obsession with clothing as a sign of worth. In The Merchant of Venice, Gratiano says, “Let me play the fool. / With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come, / And let my liver rather heat with wine / Than my heart cool with mortifying groans. / Why should a man, whose blood is warm within, / Sit like his grandsire cut in alabaster?” This moment shows disdain for the stiff, formal look of old men clinging to status through style — a subtle jab at how fashion can be used to mask decay.

Ultimately, fashion in Shakespeare’s plays becomes a kind of shorthand for class — a way for the audience to read the social map of the story at a glance. But it’s never just surface-level. The playwright constantly complicates these visuals, showing how the nobly dressed can act basely, and how those in plain clothes can speak profound truths. In this way, the outer garments often reflect — or challenge — the inner character.

Character Identity and Transformation Through Clothing

In Shakespeare’s plays, characters rarely remain static — and neither do their clothes. Fashion becomes a powerful means of transformation, allowing individuals to shift their identities, assume new roles, or blur the lines between truth and performance. Whether the change is for survival, manipulation, love, or rebellion, clothing often acts as both mask and mirror — a way to conceal one’s true self while simultaneously revealing something deeper.

Take Rosalind in As You Like It. After fleeing her uncle’s court, she transforms into “Ganymede,” donning male attire not only as protection but as a way to explore love, power, and freedom. As Ganymede, Rosalind gains control over her narrative — she challenges Orlando’s feelings, orchestrates witty games of courtship, and ultimately guides others toward romantic resolution. Her clothes don’t just disguise her gender — they give her access to a new kind of agency. She becomes more articulate, more daring, and even more self-aware in disguise than she ever was in her silk gowns at court.

Prince Hal from Henry IV Part 1 and Part 2 offers another compelling example. Born into royalty, Hal chooses to spend his early days drinking and brawling with commoners in taverns, often dressing and behaving like one of them. His “low fashion” is a strategic choice — a way to hide in plain sight and study the realm he’ll one day rule. But as the play progresses, he sheds that disguise. In his famous “I know you all” soliloquy, Hal makes it clear that his transformation has been calculated: he will cast off his common image and return to court as a noble, reformed king. When he appears in regal attire in Henry V, the change is not just sartorial — it’s symbolic. The clothes reflect his evolution from rebellious youth to heroic monarch.

Fashion also plays a central role in deception and mistaken identity. In Measure for Measure, Duke Vincentio disguises himself as a friar to observe the goings-on in his city. The hooded robe allows him to manipulate events behind the scenes, but it also raises questions about power and authenticity. Who is the Duke really — the man on the throne or the man in disguise?

Even villains use clothing as part of their manipulative schemes. In Othello, Iago engineers a tragic misunderstanding through the simple misplacement of Desdemona’s handkerchief — a fashion accessory turned weapon of jealousy. Though not a full disguise, the handkerchief becomes a symbol of deception, trust, and ultimately, destruction.

Through these moments, Shakespeare underscores a timeless truth: what we wear has the power to shape how we are seen, how we behave, and even how we see ourselves. Fashion is not just fabric; it’s transformation. Whether characters are running from danger, chasing desire, or climbing the social ladder, their clothes help them tell new stories — or conceal old ones.

Fashion as Satire: Mocking Trends and Fads of the Elizabethan Era

Shakespeare may have written for nobles and commoners alike, but he rarely missed a chance to poke fun at society’s obsessions — especially its obsession with appearance. In many of his plays, fashion becomes a punchline, a sign of foolishness, or a mask that barely hides vanity and insecurity. From extravagant trends to the constant need to stay “in style,” Shakespeare saw fashion not just as social currency but also as fertile ground for satire.

In Much Ado About Nothing, for example, fashion becomes a symbol of pretense and ridiculous behavior. The sharp-tongued Beatrice ridicules Benedick for trying to impress others with his appearance. She teases that he’s changed the shape of his beard and even adopted a new speech style — all to appear more “fashionable” and appealing to women. Her mockery exposes how shallow and transparent such changes are. The joke isn’t just on Benedick; it’s on anyone who alters their identity to fit fleeting trends.

Another great example comes from King Lear, where the Fool quips: “He’s mad that trusts in the tameness of a wolf, a horse’s health, a boy’s love, or a whore’s oath.” In this cynical list, fashion’s instability is echoed — the suggestion being that outward appearances (like fashionable attire or charming words) are as unreliable as nature itself. The Fool, in his patchwork motley, knows better than anyone that appearances can’t be trusted — and he uses his comic platform to critique those who take their own image too seriously.

Shakespeare also targets the male peacocks of his time — the men who prance about in exaggerated styles, adorned with codpieces, slashed sleeves, and towering ruffs. In Henry IV, Part 1, Falstaff mocks those who try to appear noble through dress alone, implying that no amount of fine clothing can make a coward brave or a scoundrel honorable. Falstaff, with his bloated body and mismatched gear, embraces his absurdity — and in doing so, becomes a kind of fashion anti-hero.

Even minor characters get in on the joke. In The Taming of the Shrew, the tailor and haberdasher scenes are comic gold — filled with exaggerated arguments over sleeve lengths, hat brims, and fashion faux pas. The dialogue is almost absurd in its detail, making a mockery of how much attention people give to style over substance. Shakespeare, it seems, is laughing not just at the characters but at society’s obsession with how one looks, rather than who one is.

By satirizing fashion, Shakespeare reveals his skepticism toward a world where identity is stitched together by fabric, trends, and the opinions of others. His plays remind us that fashion can flatter or fool — but when it becomes a substitute for character or conviction, it’s ripe for ridicule. And five centuries later, his playful jabs at vanity and trend-chasing still feel surprisingly modern.

Cosmetics and Costume on the Elizabethan Stage

To understand fashion in Shakespeare’s plays, we have to step beyond the script and into the theatre itself — where costumes and cosmetics were more than embellishments; they were essential storytelling tools. On the Elizabethan stage, clothing, makeup, and wigs helped bring characters to life, especially in an era where elaborate set designs and lighting effects didn’t exist. With just a few visual cues, the audience needed to instantly recognize who was noble, who was a villain, and who might be hiding something under all that paint and powder.

Actors often wore clothing that was exaggerated or symbolic rather than strictly realistic. Costumes were typically made from cast-off garments donated by nobles — meaning that a character like Macbeth or Hamlet might have been dressed in genuine aristocratic attire. These costumes helped the audience quickly distinguish royalty from commoners, even when the script didn’t state it outright. Sumptuous silks, velvet cloaks, and ornate accessories all signaled wealth and power.

Makeup was another crucial part of the performance, especially given the limitations of open-air theatres like the Globe. Visibility was key. White lead-based face paint — dangerously toxic by today’s standards — was commonly used to lighten the skin, creating a pale, smooth complexion associated with beauty and nobility. Rouge made cheeks stand out, and darkened eyebrows helped define facial expressions from a distance. Eye makeup and lip color were also used, though subtly, since overdoing it could edge into the comical or grotesque.

Wigs and false beards were frequently used to age actors or change their appearance between roles. Since all female roles were played by young boys, wigs and makeup helped complete the illusion of femininity. A long, curled wig might transform a boy into Juliet or Rosalind, while a mustache and hooded cloak could turn the same actor into a bearded villain or mysterious noble.

Interestingly, Shakespeare himself was aware of these theatrical devices and often wove them into the language of his plays. Characters like Hamlet and Richard III comment on appearance and disguise, knowing full well that the audience is watching a layered performance. In Hamlet, the prince famously says, “I have that within which passes show,” pointing out that even the deepest grief can be masked by theatrical “forms, moods, [and] shapes of grief.” He’s essentially breaking the fourth wall — acknowledging that all the world’s a stage, and everyone is in costume.

Sometimes, costumes were used for dramatic irony. A character might appear regal and trustworthy, but the audience would know (from dialogue or dramatic cues) that the clothing was hiding a lie. This tension between outer show and inner truth was a recurring theme, made all the more potent by the physical realities of the stage.

In short, cosmetics and costume weren’t just for show — they were part of the language of Shakespearean theatre. They helped the audience navigate complex plots, interpret characters quickly, and stay engaged in a world where transformation was always just a costume change away.

Modern Interpretations: Fashion in Contemporary Shakespeare Performances

One of the most striking things about Shakespeare’s plays is their incredible flexibility — they can be reimagined again and again, in different times, places, and styles. Nowhere is that more visible than in the way modern directors use fashion to reinterpret characters and themes. Contemporary productions often swap Elizabethan doublets and gowns for leather jackets, business suits, or combat fatigues — and far from being a gimmick, these choices can breathe fresh life into centuries-old stories.

In fact, modern dress is now a common tool for grounding Shakespeare’s work in the present. By placing Macbeth in a military dictatorship or Julius Caesar in a world of corporate boardrooms, costume becomes a visual shorthand for power, ambition, and betrayal. Audiences may not recognize a Renaissance robe, but a sharp gray suit? That says CEO, senator, or schemer instantly. Fashion becomes a translator — a bridge between Shakespeare’s words and the world we live in now.

Take Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet, for example. Set in a fictional modern Verona Beach, it featured Hawaiian shirts, punk-style armor, and flashy guns instead of swords. The film’s costumes played a major role in capturing the youthful chaos and high drama of the story. Romeo’s torn, casual look suggested emotional vulnerability; Juliet’s angelic white dress emphasized her innocence and otherworldliness. These weren’t just aesthetic choices — they helped the audience understand character dynamics without needing a history lesson.

On stage, directors often use clothing to highlight power shifts or identity crises. In some productions of Hamlet, the prince begins in tailored royal clothing and gradually unravels into a disheveled, almost ghostlike figure — his mental breakdown mirrored in the state of his clothes. In Othello, Iago might wear crisp military attire to reflect his manipulative professionalism, while Desdemona’s soft, flowing wardrobe emphasizes her vulnerability.

Gender and identity continue to be rich areas of exploration through costume as well. With increasing numbers of gender-blind and gender-swapped productions, fashion becomes a way to question traditional power structures. A female Lear in a tailored blazer, or a nonbinary Viola in androgynous clothing, opens new dimensions of meaning. The clothes these characters wear are not just costumes — they’re political and cultural statements.

And then there are productions that play deliberately with anachronism. A Much Ado About Nothing set in 1950s Italy, with swing dresses and slicked-back hair, or a Twelfth Night inspired by music festivals, complete with glitter and Doc Martens — these choices offer fresh energy while still honoring the emotional core of the plays. Shakespeare’s words remain the same, but the clothes reshape how we feel them.

Ultimately, modern fashion in Shakespeare is about access. It removes barriers, invites new interpretations, and helps today’s audiences see themselves in stories that are hundreds of years old. Fashion becomes the thread that connects past and present — proof that Shakespeare’s characters, like us, are always dressing up, dressing down, and trying to figure out who they really are.

The Cultural Legacy of Shakespearean Fashion

Shakespeare may have lived over four centuries ago, but the imprint of his fashion-conscious storytelling still lingers — not only on the stage, but across literature, theatre, and popular culture. From iconic costumes to the very language we use to talk about clothing, the legacy of fashion in Shakespeare’s world has proved both enduring and adaptable.

One of the most immediate places we see this influence is in theatre. Theatrical costume design continues to draw on the visual codes established during Shakespeare’s time. The contrast between nobility and commoners, the use of color to convey mood, the transformation of characters through costume — all of these elements remain foundational in stagecraft today. Shakespeare didn’t invent theatrical costume, but his plays helped cement its role as a storytelling device rather than just an aesthetic accessory.

Moreover, certain Shakespearean costumes have become almost mythic in their own right. Think of Hamlet’s dark, introspective attire — now a visual shorthand for the brooding intellectual. Or Lady Macbeth’s regal gowns, often reinterpreted as symbols of ambition, seduction, and inner turmoil. These images recur not just in theatrical productions but in books, films, fashion editorials, and Halloween costumes. They’ve become archetypes — instantly recognizable, endlessly reinvented.

In literature, the idea of fashion as a reflection of identity, morality, or status — something Shakespeare mastered — has been passed down through generations of writers. From Jane Austen’s carefully described ball gowns to the rebellious styles of punk protagonists in modern novels, fashion remains a vital way to express character. The relationship between clothing and class, image and reality, continues to be explored in ways that echo Shakespeare’s approach.

Pop culture, too, is full of Shakespearean fashion echoes. Modern film adaptations like 10 Things I Hate About You (based on The Taming of the Shrew) or She’s the Man (Twelfth Night) use clothing to highlight transformation, gender dynamics, and teenage identity crises — much like the original plays. Even high fashion isn’t immune: designers have frequently drawn inspiration from Shakespearean themes and aesthetics. Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood, and John Galliano, among others, have incorporated Elizabethan ruffs, corsetry, and theatrical silhouettes into their collections, fusing historical costume with contemporary edge.

Beyond the runway, Shakespeare’s legacy appears in how we talk about fashion itself. Phrases like “clothes make the man” or “all that glitters is not gold” have roots in the playwright’s work, subtly shaping our cultural understanding of appearance and substance.

Ultimately, Shakespeare’s use of fashion wasn’t just about visual spectacle — it was about power, identity, illusion, and transformation. He understood that clothing tells a story, and that what we wear can reveal (or conceal) who we are. That insight remains strikingly relevant today, in an age still obsessed with image and performance. Whether in a high school production or a Netflix reimagining, the threads of Shakespearean fashion continue to weave their way through

our cultural fabric.

Conclusion

In conclusion, fashion in Shakespeare’s plays is far more than a mere detail of costume or appearance; it is a dynamic tool for storytelling, symbolizing identity, transformation, and the complex interplay between appearance and reality. Through his clever use of clothing, Shakespeare explores issues of class, gender, power, and deception, allowing characters to reinvent themselves, disguise their true intentions, or reveal hidden truths. Whether through the witty cross-dressing in Twelfth Night, the symbolic use of royal garments in Macbeth, or the transformative power of Prince Hal’s sartorial choices, clothing serves as both a mask and a mirror, reflecting the characters’ innermost desires and struggles. The timeless relevance of these themes in modern productions and interpretations of Shakespeare’s work underscores how deeply fashion continues to shape our understanding of identity and society. Ultimately, Shakespeare’s nuanced approach to fashion reveals that what we wear is not just about the outer shell — it is an intrinsic part of who we are, how we are perceived, and the stories we choose to tell.